- Home

- Setting Writing

- In the Setting of Meaning

In the Setting of Meaning

Setting is the language of the story, made visual. The moment the reader steps into your world, the environment begins to communicate meaning. A well-crafted setting allows symbolism to arise naturally, letting the world reinforce its own themes, emotional tones, and character arcs.

To understand how setting carries meaning, we will look at several core areas that shape how setting carries meaning.

In the Setting of Meaning for a Character's Mind

Environments are extensions of your characters. The setting can mirror, contrast, or foreshadow what is happening inside a character's mind.

A confident character walking through a sunlit plaza suggests psychological freedom. A guilt-ridden character traveling through a barren wasteland becomes a metaphor for emotional desolation as cracks begin to form in the character's psyche.

Through the environment acting as an emotional mirror, the reader is able to empathize with the character. Using setting to reveal a character's inner conflict provides room for the reader to step inside the shoes of the character and act as more than an observer.

Symbolism In the Setting of Meaning

Many tools in your world can hold symbolic weight, but location is a strong way to reinforce your story's central themes.

In a story about ambition, towering spires and unreachable heights echo the theme. In a story where decay and moral corruption are central, the city is in peril of crumbling at the slightest touch.

In Qualx, the layered vertical strata of the city symbolizes the separation of beings through Life Rights and shows how groups are starkly divided by class.

When setting embodies your themes, readers are able to absorb the subtext of your narrative without it needing to be explained outright. Symbolic consistency in your story is key to keeping the meaning understandable.

Visual Contrast in the Setting of Meaning

As your environment shifts visually, the audience is able to immediately understand something in the narrative has changed.

When the once-hostile desert begins to bloom, it can become clear that the protagonist has reconciled their past. When a character moves from a cramped, low-light district into the blinding expanse of a neon-saturated skyway, it implies that the character's arc has reached a turning point. Beyond symbolism, setting also communicates through contrast.

Visual contrast is one of the most efficient ways to show emotional shifts, like moving from danger to safety. Even the same element (such as painfully close buildings) may represent safety for one character but danger for another. Contrast can also communicate power imbalance or the shift from hope to despair, allowing each character to filter the world in their own way.

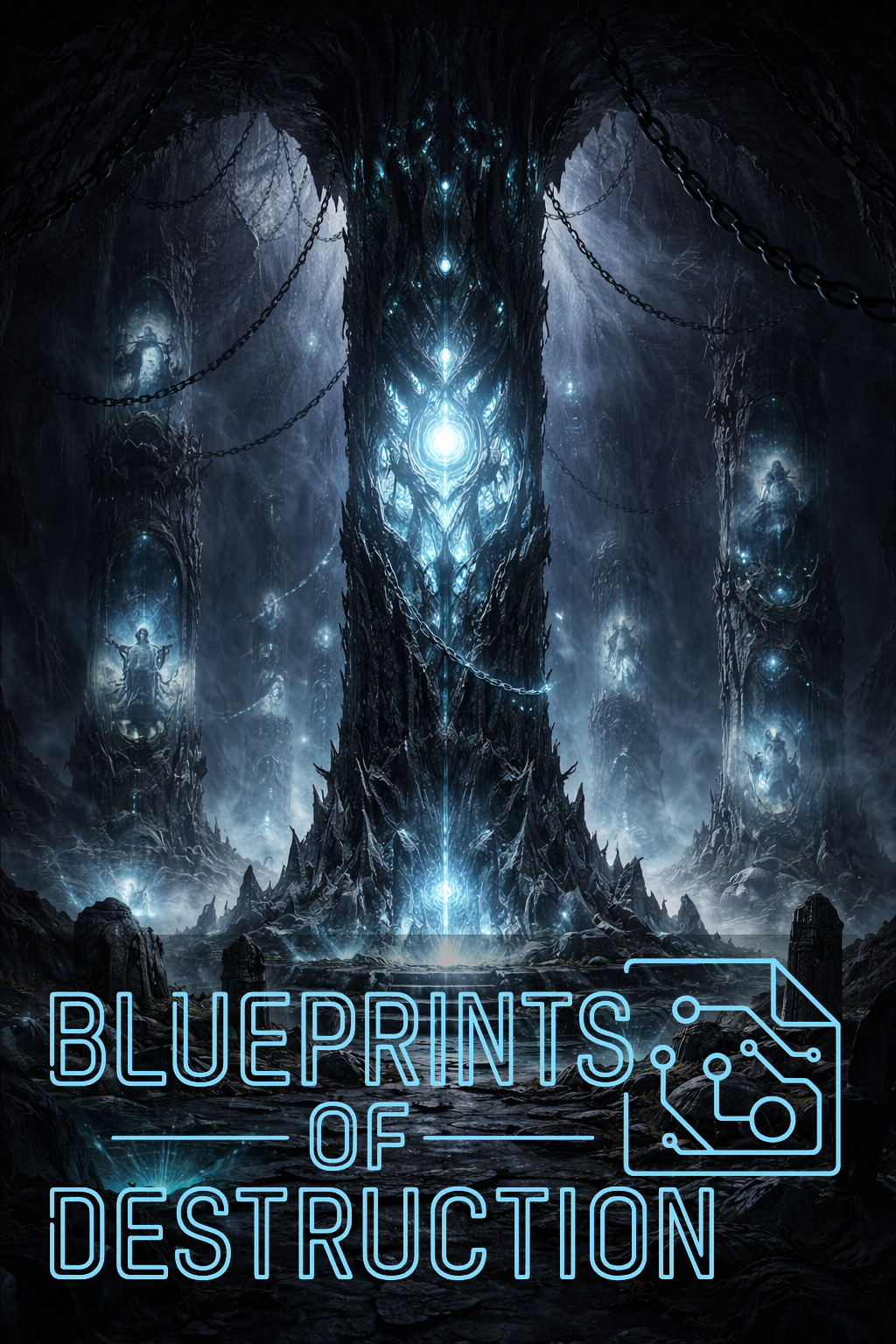

Just as setting can use visual contrast as a signal, it can also provide iconic visual anchors. Unique and recognizable environments make stories memorable and help trigger symbolic recall.

A mind-pillar cavern, representing memory, history, and danger. A high-altitude level in Qualx as it represents aspiration and transcendence. Prominent symbolism can become a kind of shorthand.

Whenever the reader returns to that place, the associated meaning is indelibly attached.

Culture in the Setting of Meaning

Setting can visually convey cultural values without exposition.

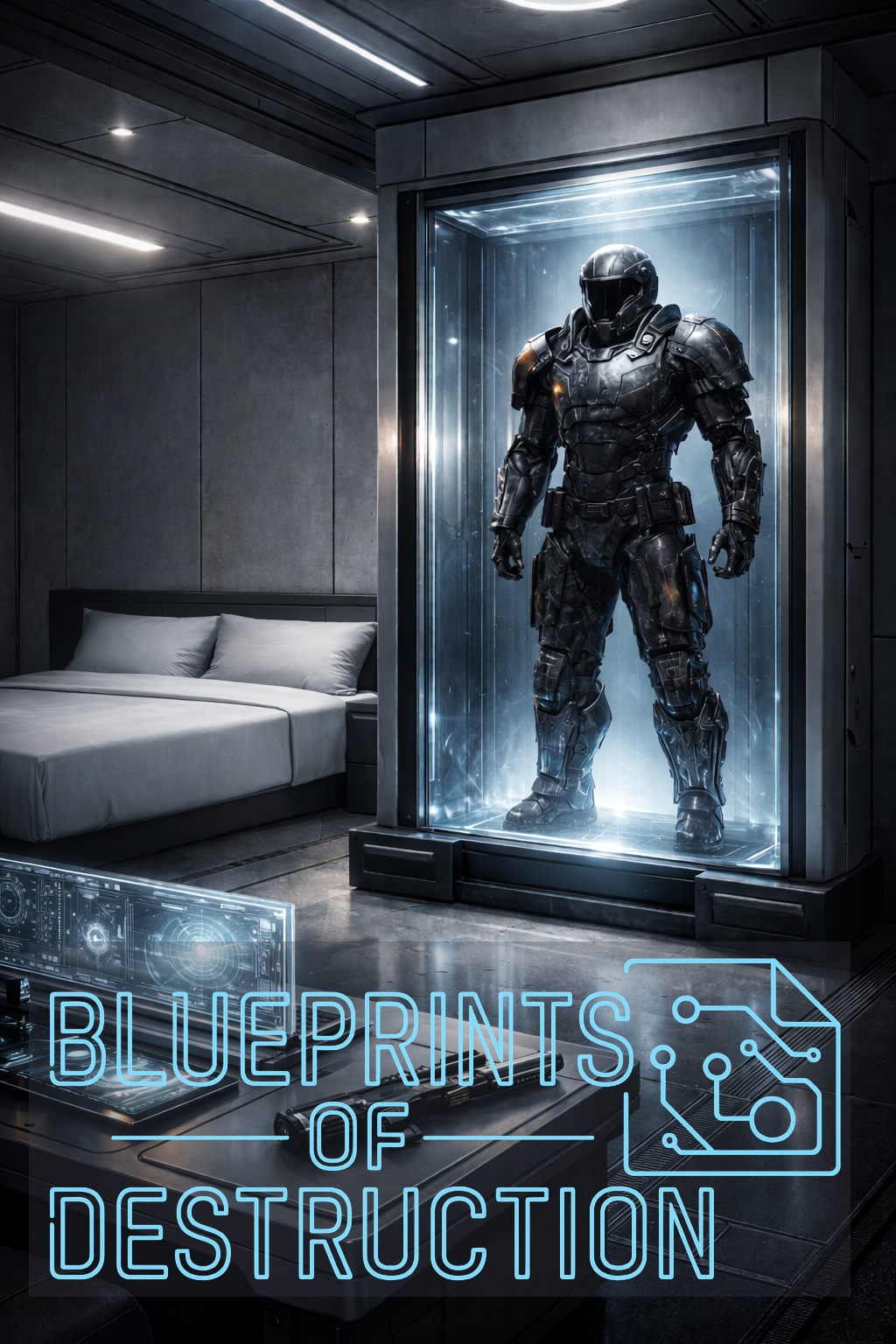

A Guild Interpreter's pristine room, battle-scarred armor as its sole decoration, acts as both a historical record and communicates the order and perfectionism demanded of him by his Archon. Each interconnected Kuma'an data garden symbolizes the living communication inside the quad-city.

Plot Mechanics in the Setting of Meaning

Setting does more than show where your story takes place; it can also show how your world works. When your world contains unique elements, like systems, rules, or technologies, the environment becomes a natural place to teach the reader these systems without stopping the narrative to explain why.

For example, the tiers of Life Rights in Qualx become clear long before anyone explains them directly. A reader can see the difference between the grim, dark, and crowded lower tiers and the bright heights above. The vertical climb of the city mirrors the social climb some characters dream of.

The environment shows the rules before the characters ever speak them.

When setting reveals a system visually through structure, color, shape, behavior, or change, the audience begins to understand the mechanics of your world on their own. The reader doesn't need a lecture. They simply learn from seeing the rules in action.

Cues through setting help your audience grasp your world's logic through visual storytelling. The environment becomes a living diagram, showing how the story's inner workings are built, maintained, and challenged.

From Abstract to Concrete

Some ideas in storytelling are intangible: grief, freedom, guilt, betrayal. Setting gives you a way to turn these invisible concepts into something the reader can feel and picture with clarity.

When an abstract idea becomes a concrete object, image, or location, it becomes something the reader can hold.

A broken bridge is no longer a mere bridge. It becomes the physical embodiment of betrayal, separation, and loss.

A locked door is fear, secrecy, and isolation in corporeal form.

Concrete symbols allow readers to attach their own complex emotions to your world. They recognize the metaphor even if they don't consciously analyze it. Setting becomes a shared emotional language between writer and reader.

This technique is especially effective when the same setting appears more than once. A character returning to an old home might notice how different it feels because they are different. A formerly terrifying battlefield may appear peaceful to the character after they have undergone internal healing.

When your abstract ideas take on the physical, the setting moves the story from the mind to the senses, and that is where the deepest impact can happen.

Readers feel the meaning before they analyze it.

Theme, when paired with setting, acts as an amplifier. It takes the magnifying glass that was on the character, and turns it to the reader, asking them to explore their own perceptions. It is a metaphor that turns ideas into images, emotion, and story itself. It is the anchor that keeps the storytelling firmly cemented in believability.

Setting is the quiet storyteller. It uses light, color, and space to share ideas that characters cannot say out loud. When you choose your setting with purpose, your world becomes more than a place. It becomes a guide.

The world begins to show feeling and meaning as it lets the reader experience the story and not just see it on the page. The setting becomes a companion that helps the reader understand the message.

When a story is built with care, the setting speaks for you in a powerful way.

Related Pages for Setting

Setting to Establish Laws and Internal Logic

Setting to Influence Pacing and Structure

Setting to Support Symbolic and Visual Storytelling